Abstract

Arctic permafrost stores vast amounts of methane (CH4) in subsurface reservoirs. Thawing permafrost creates areas for this potent greenhouse gas to be released to the atmosphere. Identifying ‘hot spots’ of methane flux on a local scale has been limited by the spatial scales of traditional ground-based or satellite-based methane-sampling methods. Here we present a reliable and an easily replicable design using only off-the-shelf, cost-effective methane sensor components and an Unmanned Aerial System (UAS). Our results demonstrate the high efficiency of the design and the advantages of this methodology for environmental methane studies that are subjected to the high spatial variability of methane levels. On Barter Island, NE Alaska, we noted spikes in CH4 concentrations coincident with topographic features or anomalies. Such spikes may be attributed to enhanced land/air transfer and may reveal zones of high methane production and/or minimal oxidation in areas of thermoerosional gullies along thawing coastal zones. Thermoerosional gullies represent hotspots that release significantly higher levels of methane than the surrounding areas, thus suggesting that point sampling is inadequate in characterizing methane releases and that increasing rates of permafrost thaw may result in increasing point sources of high CH4 emissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The permafrost landscape of the Arctic shoreline is one of the most dramatically changing environments in the world. Despite the fact that Arctic permafrost coastlines represent 34% of Earth’s coast and are affected by permafrost [1], the physical processes and mechanisms that drive change along these coastlines remain poorly understood [2, 3]. Along the Arctic shoreline, coastal erosion is expected to dramatically increase over the next decades due to the combined effect of longer and warmer thawing seasons, declining sea-ice cover that allows larger waves and storms to collide with the coastline at both longer durations and at higher coastal elevations. With this heightened erosion one can expect that constituent fluxes both into the sea and air will also increase over time.

Erosion rates appear to be increasing along some sections of the Arctic coast [4, 5] reaching up to 25 m/year [6]. This has resulted in an annual efflux of 14 Tg of particulate organic carbon into the coastal ocean [7]. This carbon flux is of equal magnitude as the annual delivery from all Arctic rivers, or the vertical net methane (CH4) emissions from terrestrial permafrost [8, 9].

While it is known that thawing permafrost creates up new areas for methane emissions, the identification of these pathways using traditional ground-based or satellite-based methane-detecting methods has been both challenging and insufficient [10]. In coastal permafrost environments, pathways from which methane can be released into the atmosphere [11] are typically (a) the top half meter of soil that thaws each summer (active layer), especially from thermoerosional drainages or meltwater lakes where microbes are most active; (b) escape conduits from disintegrating permafrost caps and/or ice wedges; and (c) from thawing offshore permafrost and gas hydrate dissociation (Fig. 1). Here we focus our efforts on the first of the above three pathways, where high methane fluxes are the result of thawing permafrost that is associated with saturated systems such as thermokarst bogs, fens [12,13,14] and as in this study thermoerosional gullies [15, 16].

Spatial identification and quantification of CH4 efflux hotspots may serve a twofold purpose along coastal bluffs. First, quantifying CH4 efflux from hotspots is essential for accurate methane budgets. Secondly, these hotspots could also indicate areas of lower soil stability, thereby identifying coastal sites highly vulnerable to erosion. Identification of methane pathways may therefore help gain better local insights on permafrost integrity and help with erosion prediction models.

Currently, spatial methane distribution in the Arctic is being recorded mostly with top-down methods by several different means—all of which come with major drawbacks: (1) tower station measurements have a sparse spatial coverage and cannot identify individual methane sources; (2) satellite measurements can reveal large scale atmospheric background signals but give little indication on the ground-based sources of methane sources; (3) airplane-based measurements can only be carried out at a minimum height of ~ 100 m and are not as accurate as in situ data. All of the above methodologies are associated with significant costs unattainable for most institutions and stakeholders (e.g. [17]).

Until recently, methane measurements with systems sensitive to parts-per-billion levels were also confined to large, heavy and expensive laboratory equipment; now, a new class of significantly more cost-effective and lighter tunable diode-laser using absorption spectroscopy [18] allows for the measurement of methane using small Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS). While few of these methane-detection systems have been developed (i.e. [19, 20]) none have aimed to create an off-the-shelf, cost effective UAS design. An overview of the challenges and limitations of using small UAS systems to monitor methane and other atmospheric gases has been compiled by Villa et al. [21]. While this manuscript focuses on the application of an unmanned methane sensor in a very remote, largely undisturbed location north of the Arctic circle, where permafrost is thawing, the proposed system could also be utilized for more urban environments and for pipeline leak detection. Emran et al. [22] for example, have recently demonstrated the feasibility and advantages of UAS-based methane monitoring for grass-topped landfill degassing, and Bretschneider et al. [23] showed how such a system could detect leaks in pipelines. The methane laser sensor used herein was first developed in 1992 [24] and became commercially available in 2013 [25]. The sensor has been shown to function in a natural environmental setting to demonstrate time variation of low CH4 concentrations over rice paddies [26] or small ponds and ditches [27]. We here present the design and components of a CH4—UAS system.

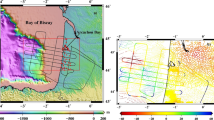

In this paper, we demonstrate our efforts to detect methane being emitted from thawing coastal permafrost and map these concentrations. Our study was carried out along the coastal bluff environment of Barter Island, AK, which is part of a larger Arctic coastal erosion investigation study by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS; i.e. [28,29,30]).

2 Methods

2.1 The UVA-platform

In this study the 3DR Solo was used as the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) platform (Fig. 2). It was chosen because it is currently the only small UAV platform that has been approved for use by the USGS for research purposes by the Department of the Interior. Although not ideal due to its low payload of 700 g the rotary-wing quadcopter is inexpensive (< $500 USD) and was upgraded with a highly accurate professional grade GPS system utilizing European (Galileo), Russian (GLONASS) and North American (GPS) positional information. The GPS system has a Horizontal Dilution Of Precision (HDOP) of 0.6 inside the UAV [31]. At full payload and at 3–6 °C, the maximum achieved flight-time was between 8 and 10 min. For future flight configurations, we highly recommend utilization of a UAV platform that has a greater payload and a longer flight time, but similar GPS accuracy and flight stability.

The vibration dampening methane sensor mount was 3D-printed (Fig. 2) and attached to the central Accessory Bay, the area behind the gimbal under the 3DR Solo. It is intended for secondary accessories, including additional communications hardware and other high power devices [32]. Total cost for UAS and 1 month sensor rental was < $2500.

2.2 The methane sensor

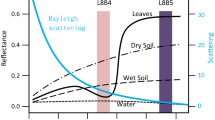

The Pergam Methane mini-G (SA3C50A) is currently the only commercially available methane sensor that has low enough weight and high enough range (1–50,000 ppm) and sensitivity (1 ppm) as well as a fast enough recording speed (10 Hz) to allow for remote sensing use (Table 1). The sensor uses Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy and a semiconductor laser for methane detection [18] and is advertised by the manufacturer for aerial use over non-flat surfaces such as grass-covered landfills. While the strongest absorption bands for methane exist at ~ 3300 nm and ~ 7700 nm these bands are overlapped by absorption bands of water vapor and CO2. In order to avoid this overlap, a weaker band frequency of 1653 nm has been determined to be free of overlap by absorption bands of water vapor and CO2 (see “Appendix”, Fig. 8). Nonetheless it should be mentioned that tunable laser absorption spectroscopy is an ongoing research area and others [33] have made clear that overlap of bands can occur in field observations if the sensor is not finely tuned to the specific band. Consequently, the detector relies on transmitting a laser beam with a frequency tuned precisely to the absorption characteristics of methane gas (1653 nm) [34]. The integrated concentration of methane between the sensor and the target point is measured by transmitting a detection laser beam towards the target point, and then detecting a fraction of the diffusely reflected beam from that target point. The measured value is expressed by an inventory (ppm*m) which is the methane concentration (ppm) multiplied by the distance (m) between the sensor and its target. All measurements were normalized to 1 m distance to reflect the more common volumetric ppm values found in atmospheric sciences literature. Consequently, the measurements presented herein represent path-averaged concentrations in ppm, which implies that ground concentrations could feasibly be higher (Fig. 3).

UAV-based tunable diode laser spectrometry. The system calculates path integrated methane concentration in ppm*m. This value is then divided by the distance to the reflection surface to get path-averaged concentration in ppm which represents the more common notation standard (e.g. [35]). In example A, this procedure ((150 + 2+2 + 2+2)/5) yields a concentration of 31.6 ppm, while B ((2 + 30 + 2+2 + 2)/5) has a concentration of 7.6 ppm. In the illustration ~ 2 ppm/m was chosen to present a typical CH4 background concentration

Methane concentration measurements were updated at a rate of 10 Hz. In addition to the internal calibration that the instrument undergoes during each reboot, a calibration experiment was carried out using quartz glass calibration gas cells at varying distances and concentrations. While the manufacturer lists the CH4 levels with a ± 10% accuracy our calibration experiment suggested an accuracy of ± 30–40%. Calibration curves are shown in the “Appendix”. All data were GPS referenced and stored via a standard Bluetooth link on a UAV mounted Android OS device (Fig. 2).

2.3 Flight plans and post processing

Automatic flight paths were created using Mission Planner [36] and executed to fly at a continuous speed of 3 m/s. A high precision Lidar-based Digital Elevation Model (DEM) [15] was used to guide the methane sensor at a constant distance of 5 m above ground. The normalization of the data to 1 m distance occurred by simply dividing the set flight elevation by five. The flight elevation was chosen in part because the sensor is most precise at distances of 5–10 m (see “Appendix”) and because it was the minimum height at which the drone could be safely operated above potential human activity. However, there was no recorded human activity nor engineering construction that could have affected the measurements within the study site. The flight paths were created to be above the flat vegetation tundra landscape, slightly inland (~ 5 m) of the coastal bluff (Fig. 5). All flights were carried out during zero to low (< 3 m/s) wind conditions and flown against the prevailing western wind direction. All human infrastructure that could potentially act as an anthropogenic methane source was downwind from our study site. This strategy was chosen in order to identify individual hotspots along the flight path rather than following a plume. Air temperatures during all flights were at a constant 2 °C and between 35 and 45% humidity as determined by the nearby (located 650 m away) airport weather station. The methane sensor automatically marks data that was recorded with a below minimum reflected energy as containing an error such as over bodies of water. This data was filtered from the utilized dataset following a previously published MATLAB (R2007a) methodology described by Emran et al. [22]. Visualization of the methane data was carried out using Google Earth software but can be performed using any GIS software program.

3 Results and discussion

Field deployment of the UAS was carried out on Barter Island, Alaska between Sept. 3–5, 2017 over a near linear path of 2 km closely following the coastal bluffs. In addition to the previously performed calibration experiment in the lab (see “Appendix”), a test grid was flown at a higher altitude of 10 m over an area where permafrost was expected to be largely intact and methane levels relatively constant (Figs. 4a, 5). The purpose of this test grid was to demonstrate the functionality of the sensor in situ and establish a CH4 atmospheric baseline as well as background noise. Because atmospheric background levels are very close to the sensor’s sensitivity rating of 1 ppm, a higher altitude was chosen to allow for a greater path-integrated measurement in the background level test. The background level test flight revealed a relatively high instrument variance of 1.17 (± 56%) over 5600 measurements but also a consistent linear average of 2.06 ppm (Fig. 4a). Considering the manufacturer’s reported error range (± 10%), this value closely mirrors the average regional background measurements of 1.95 ppm for Sept., 2017 (Fig. 4b) established by the NOAA’s Global Monitoring Division [37].

a (Lower) Methane background levels from Test Grid flight (see Fig. 5 for location) were recorded as ppm × m measurements and normalized to ppm by division of the flight height of 10 m. b (Upper) Long term regional atmospheric background methane signal

Our first results from Barter Island, AK show that spatial methane distribution along the 2 km coastal path is mostly at atmospheric background levels of 2 ppm ± 35%. There are however several large methane peaks within the flown path. These peaks range between 20 and 210 ppm and are spread out along the path. After closer analysis of the surface topography it became clear that the peaks were linked with areas of high permafrost thaw and thermoerosional gullies (Fig. 5).

High methane fluxes from thawing permafrost are often associated with saturated systems such as thermokarst bogs, fens, and lakes or low centered polygonal tundra [12]. Much less research has been focused on thermoerosional gullies because they may not typically be saturated and they may represent a small fraction of the landscape. However, recent studies [15] have shown high CH4 fluxes from gullies such as ours, even if soil moisture is not changed relative to the undegraded landscape. The mechanisms driving these fluxes and the contribution of these fluxes to the overall coastal methane budget, are further issues to be resolved.

A comparison between methane hotspots and long-term coastal bluff retreat (Fig. 6) showed that the highest methane peaks could also be associated with some of the highest retreat rates along the coastal bluff. More specifically, the methane hotspots mark thermoerosional gullies, which are also areas of amplified permafrost thaw and thus can be seen as erosional hotspots along the bluff coastline. However, not all peaks correlate, which indicates that while thermoerosional gullies can be areas of lower bluff stability, the primary bluff retreat is likely caused by a combination of thermo-denudation and thermo-abrasion [38].

The main uncertainties associated with this study are caused by potential variations in the ground to sensor distance. These variations are most likely associated with non-linear movements of the UAS such as roll, tilt and yaw that are produced by flight turns and variable wind speeds and directions. While the data on off-nadir angle could not be recovered due to an overwrite, common deviations from Nadir for this UAS-class are < 15° [39, 40]. Assuming a 15° deviation from Nadir, this would lead to a maximum 3.5% increase in measured methane levels, which is significantly below the published accuracy (± 10%) or our measured accuracy (± 35%) of the instrument (Table 1, “Appendix”). Nonetheless, in order to account for this effect we included many turns in our test grid at constant flight speed (Fig. 4a) forcing yaw, tilt and roll and thus establishing a conservative measure of instrument background noise. Conversely, in the permafrost bluff survey we attempt to minimize this effect by avoiding all turns in our flight path (Fig. 5). Unfortunately, wind, fog and snow prevented additional flights during the time-limited field research campaign, and locations north of the Arctic Circle such as Barter Island are not easily accessed to allow for low-cost follow up studies. Nonetheless, with respect to future deployments, we hope to employ traditional ground-based point-sampling techniques to better quantify the relative limitation of each methodology in more detail. Additional uncertainties in our measurements may be the result of the under or over represented gullies in the DEM used in this study. Gullies ranged in depth by 1–5 m and an additional conservative ± 20% measurement error can be estimated from comparisons between field elevation observations of gullies and DEM results. While this leads to a total uncertainty of ± 55%, which is mirrored by our field observed uncertainty of ± 56%, the reported peaks found in gullies are more than 2000% above background levels (Fig. 5) and thus remain significant with these uncertainties applied.

Despite the current uncertainties, the herein presented UAV-based methodology falls inside an important spatial gap between local and regional scales that was previously difficult to bridge by existing methodologies. Methane measurements occur along a range of spatial and temporal scales (Fig. 7), from small-scale near-instantaneous measurements of emissions from individual sources (such as from a smokestack) to large-scale global assessments of annual emissions (such as from satellites). Associated with the different methane sensing technologies are major strengths and weaknesses that contribute to the applicability and scope of the produced data (Table 2).

Spatial and temporal scales associated with major methane sensing platforms and methodologies (e.g. [17])

The herein presented technology could also be used to look for areas of geological methane release and CH4 release from methane hydrates. However, in those cases, isotopic methane composition will help in answering questions of geologic methane origin. Additionally, planned future studies focusing on the onset of the thawing season are likely to answer the question if the herein presented UAS methane-detection methodology is capable at predicting erosion hotspots through early identification of methane hotspots.

Spatial methane distribution data that can be used to identify source pathways is currently still very rare and traditionally its monitoring has been reserved to large institutions capable of absorbing the associated high costs. Compared to previous efforts that collected spatial methane data in the Arctic by helicopter [41, 42], by small aircraft [10], by ground based laser scanning [43], or with a ground based solid-state trace gas sensor [44] the methodology presented herein exemplifies a significantly more affordable (< $2500) and more flexible method towards acquiring spatial methane distributions.

With the rapid commercial spread of UAVs the presented UAS system has the potential to accelerate the availability of high resolution spatial methane data through university and citizens science and thus gain significantly better insights into methane pathways and its related processes.

References

Lantuit H, Overduin PP, Couture N, Wetterich S, Aré F, Atkinson D, Brown J, Cherkashov G, Drozdov D, Forbes DL, Graves-Gaylord A, Grigoriev M, Hubberten H-W, Jordan J, Jorgenson T, Ødegård RS, Ogorodov S, Pollard WH, Rachold V, Sedenko S, Solomon S, Steenhuisen F, Streletskaya I, Vasiliev A (2012) The Arctic coastal dynamics database: a new classification scheme and statistics on Arctic permafrost coastlines. Estuaries Coasts 35:383–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-010-9362-6

Günther F, Overduin PP, Sandakov AV, Grosse G, Grigoriev MN (2013) Short- and long-term thermo-erosion of ice-rich permafrost coasts in the Laptev Sea region. Biogeosciences 10:4297–4318. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-10-4297-2013

Wobus C, Anderson R, Overeem I, Matell N, Clow G, Urban F (2011) Thermal erosion of a permafrost coastline: improving process-based models using time-lapse photography. Arctic Antarct Alp Res 43:474–484. https://doi.org/10.1657/1938-4246-43.3.474

Jones BM, Arp CD, Jorgenson MT, Hinkel KM, Schmutz JA, Flint PL (2009) Increase in the rate and uniformity of coastline erosion in Arctic Alaska. Geophys Res Lett 36:L03503. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL036205

Fritz M, Vonk JE, Lantuit H (2017) Collapsing Arctic coastlines. Nat Clim Change 7:6–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3188

Gibbs AE, Richmond BM (2017) National assessment of shoreline change—summary statistics for updated vector shorelines and associated shoreline change data for the north coast of Alaska. US Geol Surv Open-File Rep. https://doi.org/10.3133/ofr20171107

Wegner C, Bennett KE, de Vernal A, Forwick M, Fritz M, Heikkilä M, Łącka M, Lantuit H, Laska M, Moskalik M, O’Regan M, Pawłowska J, Promińska A, Rachold V, Vonk JE, Werner K (2015) Variability in transport of terrigenous material on the shelves and the deep Arctic Ocean during the Holocene. Polar Res 34:24964. https://doi.org/10.3402/polar.v34.24964

Schuur EAG, McGuire AD, Schädel C, Grosse G, Harden JW, Hayes DJ, Hugelius G, Koven CD, Kuhry P, Lawrence DM, Natali SM, Olefeldt D, Romanovsky VE, Schaefer K, Turetsky MR, Treat CC, Vonk JE (2015) Climate change and the permafrost carbon feedback. Nature 520:171–179. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14338

Koven CD, Ringeval B, Friedlingstein P, Ciais P, Cadule P, Khvorostyanov D, Krinner G, Tarnocai C (2011) Permafrost carbon-climate feedbacks accelerate global warming. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108:14769–14774. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1103910108

Kohnert K, Serafimovich A, Metzger S, Hartmann J, Sachs T (2017) Strong geologic methane emissions from discontinuous terrestrial permafrost in the Mackenzie Delta, Canada. Sci Rep 7:5828. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05783-2

Ruppel CD, Kessler JD (2017) The interaction of climate change and methane hydrates. Rev Geophys 55:126–168. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016RG000534

Turetsky MR, Kotowska A, Bubier J, Dise NB, Crill P, Hornibrook ERC, Minkkinen K, Moore TR, Myers-Smith IH, Nykänen H, Olefeldt D, Rinne J, Saarnio S, Shurpali N, Tuittila E-S, Waddington JM, White JR, Wickland KP, Wilmking M (2014) A synthesis of methane emissions from 71 northern, temperate, and subtropical wetlands. Glob Change Biol 20:2183–2197. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12580

Olefeldt D, Goswami S, Grosse G, Hayes D, Hugelius G, Kuhry P, Mcguire AD, Romanovsky VE, Sannel ABK, Schuur EAG, Turetsky MR (2016) Circumpolar distribution and carbon storage of thermokarst landscapes. Nat Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13043

Walter Anthony K, Schneider von Deimling T, Nitze I, Frolking S, Emond A, Daanen R, Anthony P, Lindgren P, Jones B, Grosse G (2018) 21st-century modeled permafrost carbon emissions accelerated by abrupt thaw beneath lakes. Nat Commun 9:3262. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05738-9

Yang G, Peng Y, Olefeldt D, Chen Y, Wang G, Li F, Zhang D, Wang J, Yu J, Liu L, Qin S, Sun T, Yang Y (2018) Changes in methane flux along a permafrost thaw sequence on the Tibetan Plateau. Environ Sci Technol 52:1244–1252. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b04979

Abbott BW, Jones JB (2015) Permafrost collapse alters soil carbon stocks, respiration, CH4, and N2O in upland tundra. Glob Change Biol 21:4570–4587. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13069

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine (2018) Improving characterization of anthropogenic methane emissions in the United States. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.; ISBN 978-0-309-47050-6

Werle PW (2004) Diode-laser sensors for in situ gas analysis. In: Laser in environmental and life sciences. Springer, Berlin, pp 223–243. ISBN: 3-540-40260-8

Smith BJ, John G, Christensen LE, Chen Y (2017) Fugitive methane leak detection using sUAS and miniature laser spectrometer payload: system, application and groundtruthing tests. In: 2017 International conference on unmanned aircraft systems (ICUAS); IEEE, pp 369–374

Golston LM, Tao L, Brosy C, Schäfer K, Wolf B, McSpiritt J, Buchholz B, Caulton DR, Pan D, Zondlo MA, Yoel D, Kunstmann H, McGregor M (2017) Lightweight mid-infrared methane sensor for unmanned aerial systems. Appl Phys B 123:170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-017-6735-6

Villa T, Gonzalez F, Miljievic B, Ristovski Z, Morawska L (2016) An overview of small unmanned aerial vehicles for air quality measurements: present applications and future prospectives. Sensors 16:1072. https://doi.org/10.3390/s16071072

Emran BJ, Tannant DD, Najjaran H (2017) Low-altitude aerial methane concentration mapping. Remote Sens 9:823. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs9080823

Bretschneider TR, Shetti K (2014) UAV-based gas pipeline leak detection. In: Asian conference on remote sensing at Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar, pp 1–6

Uehara K, Tai H (1992) Remote detection of methane with a 166-μm diode laser. Appl Opt 31:809. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.31.000809

Pergam and Tokyo Gas Engineering Co. Operation manual for laser methane mini-G. https://www.crowcon.com/product/download/640/SA3C50A+Manual.pdf

Matsumi Y, Hidemori T, Nakayama T, Imasu R, Dhaka SK (2016) Measuring methane with a simple open-path gas sensor. Int Soc Opt Photonics. https://doi.org/10.1117/2.1201601.006283

Holmgren MA, Hansen MN, Reinelt T, Westerkamp T, Jørgensen L, Scheutz C, Delre A (2015) Measurements of methane emissions from biogas production data collection and comparison of measurement methods. Energiforsk 158:1–139. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1007.4087

Gibbs AE, Nolan M, Richmond BM, Kinsman N, Richmond BM (2015) Evaluating changes to arctic coastal bluffs using repeat aerial photography and Structure-from-motion elevation models. In: The proceedings of the coastal sediments 2015; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, pp 1–14

Swarzenski PW, Johnson CD, Lorenson TD, Conaway CH, Gibbs AE, Erikson LH, Richmond BM, Waldrop MP (2016) Seasonal electrical resistivity surveys of a Coastal Bluff, Barter Island, North Slope Alaska. J Environ Eng Geophys 21:37–42. https://doi.org/10.2113/JEEG21.1.37

Erikson LH, Storlazzi CD, Jensen RE (2011) Wave climate and trends along the Eastern Chukchi Arctic Alaska Coast. In: Solutions to coastal disasters 2011; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, pp 273–285

MRobotics Technical Information for GPS chipset mRo u-Blox Neo-M8 N. https://store.mrobotics.io/product-p/gps001-mr.htm. Accessed 6 Jan 2018

3D Robotics 4.2. The Accessory Bay. https://dev.3dr.com/hardware-accessorybay.html. Accessed 26 Aug 2018

Khan A, Schaefer D, Tao L, Miller DJ, Sun K, Zondlo MA, Harrison WA, Roscoe B, Lary DJ (2012) Low power greenhouse gas sensors for unmanned aerial vehicles. Remote Sens 4:1355–1368. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs4051355

Fukuchi T (2012) Gas sensing using laser absorption spectroscopy. In: Fukuchi T, Shiina T (eds) Industrial applications of laser remote sensing. Bentham Science Publishers: Chiba University, Japan, 2012; pp 37–59. ISBN: 9781608053407

Liebetrau J, Reinelt T, Agostini A, Linke B (2017) Methane emissions from biogas plants greenhouse gas balance of electricity produced. In: Murphy JD (ed) IEA Bioenergy; ISBN: 9781910154359

ArduPilot Mission Planner Home

Dlugokencky EJ, Lang PM, Masarie KA, Crotwell AM, Crotwell MJ. Database for atmospheric methane dry air mole fractions from quasi-continuous measurements at Barrow, Alaska and Mauna Loa, Hawaii. ftp://aftp.cmdl.noaa.gov/data/trace_gases/ch4/insitu/surface/. Accessed 5 Aug 2018

Gibbs AE, Richmond BM, Erikson L, Jones BM (2018) Long-term retreat of coastal permafrost bluffs, Barter Island, Alaska. In: 5th European Conference on permafrost; EUCOP5: Chamonix, France, vol 1, pp 1–2

Gašparović M, Jurjević L (2017) Gimbal influence on the stability of exterior orientation parameters of UAV acquired images. Sensors 17:401. https://doi.org/10.3390/s17020401

Goldbergs G, Maier S, Levick S, Edwards A (2018) Efficiency of individual tree detection approaches based on light-weight and low-cost UAS imagery in Australian Savannas. Remote Sens 10:161. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10020161

Dzikowski M, Klyashitsky A, Jaeger W, Tulip J (2009) Open path spectroscopy of methane using a battery operated vertical cavity surface-emitting laser system. In: Vallée R (ed), p 73861H

Fix A, Ehret G, Hoffstädt A, Klingenberg HH, Lemmerz C, Mahnke P, Ulbricht M, Wirth M, Wittig R, Zirnig W (2004) Charm—a helicopter-borne lidar system for pipeline monitoring. Eur Sp Agency Spec Publ ESA SP 1:45–48

Gibson G, Van Well B, Hodgkinson J, Pride R, Strzoda R, Murray S, Bishton S, Padgett M (2006) Imaging of methane gas using a scanning, open-path laser system. New J Phys 8:26. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/8/2/026

Eugster W, Kling GW (2012) Performance of a low-cost methane sensor for ambient concentration measurements in preliminary studies. Atmos Meas Tech 5:1925–1934. https://doi.org/10.5194/amt-5-1925-2012

Rothman LS, Gordon IE, Babikov Y, Barbe A, Chris Benner D, Bernath PF, Birk M, Bizzocchi L, Boudon V, Brown LR, Campargue A, Chance K, Cohen EA, Coudert LH, Devi VM, Drouin BJ, Fayt A, Flaud J-M, Gamache RR, Harrison JJ, Hartmann J-M, Hill C, Hodges JT, Jacquemart D, Jolly A, Lamouroux J, Le Roy RJ, Li G, Long DA, Lyulin OM, Mackie CJ, Massie ST, Mikhailenko S, Müller HSP, Naumenko OV, Nikitin AV, Orphal J, Perevalov VI, Perrin A, Polovtseva ER, Richard C, Smith MAH, Starikova E, Sung K, Tashkun SA, Tennyson J, Toon GC, Tyuterev VG, Wagner G (2013) The HITRAN2012 molecular spectroscopic database. J Quant Spectrosc Radiat Transf 130:4–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2013.07.002

Knights Optical Material specifications for fused quartz JGS3 with 185–3500 nm transmission. https://www.knightoptical.com/_public/documents/1382532741_irmaterialirfusedquartzjgs3opmi-jgs3.pdf. Accessed 6 Jan 2018

Acknowledgements

Funding for this research was provided by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Coastal and Marine Geology Program and the U.S. Geological Survey’s Mendenhall Program. We thank the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services for their local support. We also thank C. Johnson and T. Lorenson for assistance with instrument deployment and data collection. The IAEA is grateful for the support provided to its Environment Laboratories by the Government of the Principality of Monaco. A special thanks goes to the community of Kaktovik for their continued support for scientific research. We do not intend to claim that the methane sensor’s manufacturer accuracy statement or any other statements by the manufacturer are incorrect as differences in laboratory setups and methodologies can lead to different results. Data on which this paper is based are availabe for download at https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.898636. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

The methane sensor used in this study has an internal system check and calibration procedure built in upon startup using a built-in reference cell. While the manufacturer ensures that this yields a reliable and consistent performance, the exact internal procedure is proprietary. The laser used in this study is finely tuned to 1.653 µm. At this wavelength the absorption of CH4 does not overlap with H2O or CO2 and can thus be used to discretely quantify CH4 amounts (Fig. 8).

Comparison of CH4, H2O and CO2 laser wavelength absorption [45] at 3 °C. Areas of wavelength absorption overlap are shown in shaded bars

In order to check the validity of the sensor’s measurements a calibration experiment was designed using infrared fused quartz glass to build a gas-floodable cylindrical spectrophotometer cell. The IR fused quartz is manufactured by the fusion of naturally occurring crystal quartz in an electric vacuum furnace. This process results in the lowest possible water content (OH) of less than 5 parts per million [46]. These IR fused quartz cells have excellent transmission from 260 nm thought to 3500 nm and low striae and inclusion content to limit absorption and refraction. The test results confirmed the functionality of the sensors internal calibration procedure (Fig. 9).

Methane sensor variability test using ambient air. Approximately 1200 measurements of ambient air (~ 2 ppm) were taken at each distance (2, 5, 10, 15 and 20 m). Results showed that with increasing distance variability of the sensor increases while the mean remains fairly consistent (r2 = 0.91). The average percent deviation from the mean is 16%. When converted to standardized units (1 m distance) the spread in ppm between the maximum and minimum readings at each distance is ~ 4.2 ppm spread at 2 m, ~ 1.5 ppm spread at 5 m, ~ 1.3 ppm spread at 10 m, ~ 2.1 ppm spread at 15 m and ~ 2.6 ppm spread at 20 m. The spread indicates that the sensor is most precise at distances of 5–10 m with a ± 30–40% accuracy which guided the decision to perform field operations at a low altitude of 5 m

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oberle, F.K.J., Gibbs, A.E., Richmond, B.M. et al. Towards determining spatial methane distribution on Arctic permafrost bluffs with an unmanned aerial system. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 236 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0242-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-0242-9